MARRAKECH

April 2023

Most days in the medina of Marrakech, the old town bustles with activity and pulsates with people. Motorbikers buzz through the city on forest green Yamahas, nagging and nudging pedestrian traffic to move out of the way. Countless cats navigate the streets looking for spare food, while residents stop at food stalls for skewers, sweets, sandwiches, and “magic bread.” Tourists and travelers—like us—look lost in the labyrinth, trying to make sense between the virtual blue dot on our Google Maps and a physical environment that is, well, unmappable. Vendors in the souks sell everything under the Moroccan sun and invite the blue-dot-dependent tourists to buy something for a very good price.

Outside, in the souks, the medina is loud and chaotic and alive and magical.

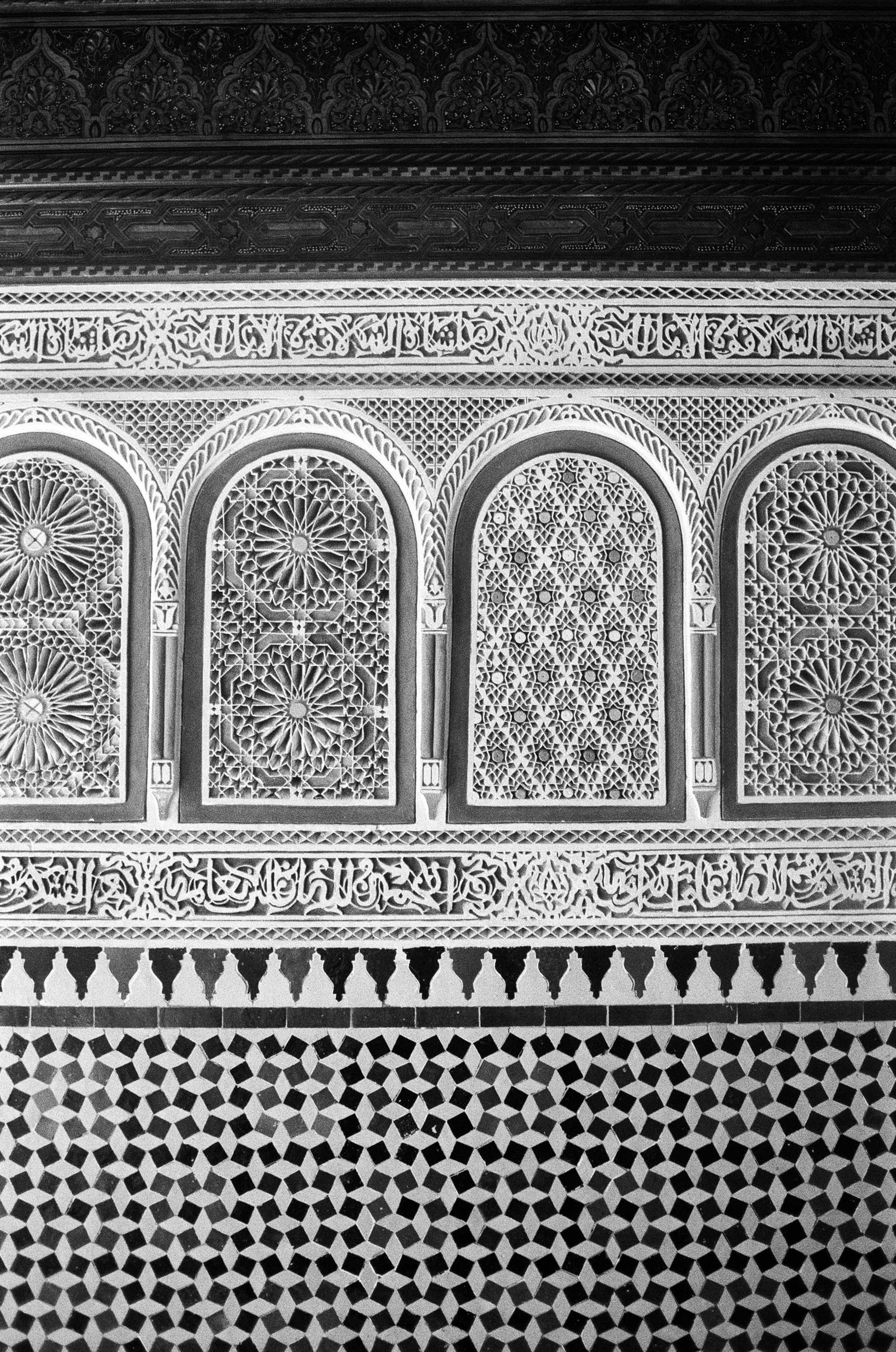

Inside, beyond the doors, the noise numbs into a spacious quiet. Cramped corridors give way to expansive courtyards and hidden plazas, where gardens are growing and people are murmuring. Dusty, dark-wooden doors open into bright white spaces with immaculate zellige tiling, combining greens and blues and yellows in decadently detailed patterns.

Our visit in the city was a dance between these outside and inside worlds.

Outside, in the souks, the medina is loud and chaotic and alive and magical.

Inside, beyond the doors, the noise numbs into a spacious quiet. Cramped corridors give way to expansive courtyards and hidden plazas, where gardens are growing and people are murmuring. Dusty, dark-wooden doors open into bright white spaces with immaculate zellige tiling, combining greens and blues and yellows in decadently detailed patterns.

Our visit in the city was a dance between these outside and inside worlds.

The mornings began with breakfast on the roof of our riad: breads and small spreads. A first cup of mint tea. At least three more would follow.

The first two days of our trip coincided with the final two days of Ramadan. While many residents were fasting, the buzz of the city was continuous—paused by brief interludes of prayer, broadcast over medina-wide loudspeakers.

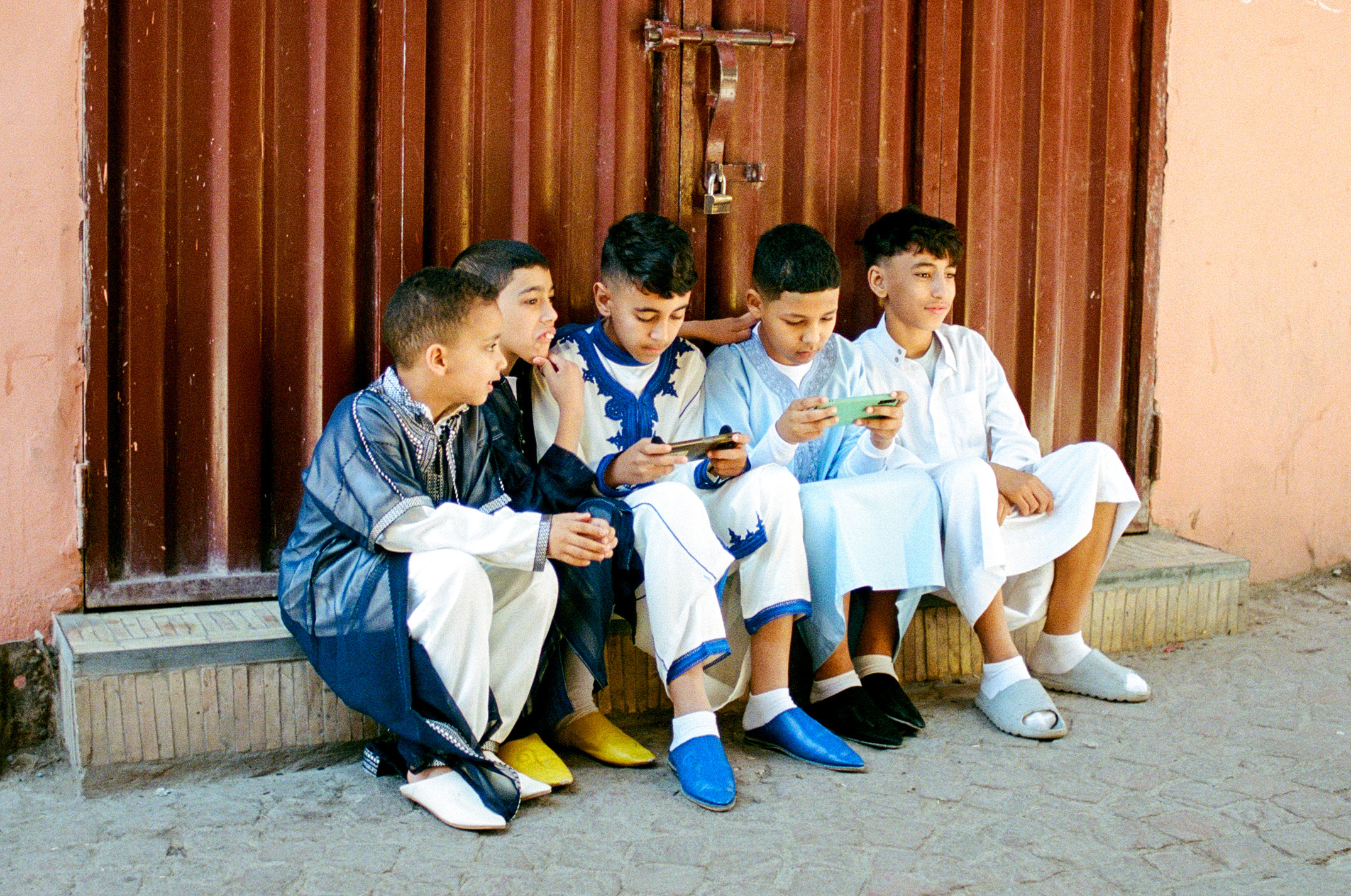

In advance of Eid-al-Fitr, the festival that celebrates the end of the holy month, preparations were in full swing. Haircuts, shopping, groceries, bathing—all the essential last-minute errands and rituals before a celebration.

The main square, where food vendors and traders of all kinds congregate, was quiet during the day. After sundown, closer to 10pm, the central plaza enlivened once again with people ending their daily fast.

In advance of Eid-al-Fitr, the festival that celebrates the end of the holy month, preparations were in full swing. Haircuts, shopping, groceries, bathing—all the essential last-minute errands and rituals before a celebration.

The main square, where food vendors and traders of all kinds congregate, was quiet during the day. After sundown, closer to 10pm, the central plaza enlivened once again with people ending their daily fast.

When Eid-al-Fitr did finally come, the medina transformed. At first, the souks locked their doors. The streets emptied into a surreal quiet—devoid of the typical commerical hustle and bustle. It was said that many residents had returned to their families, leaving the medina to go visit nearby towns. The city retreated behind closed doors, folding into its indoor spaces.

The emptiness did not last long. Soon, and suddenly, the city emerged into the public spaces—this time, wearing bright and beautiful clothes and colorful pointed shoes. Residents spilled into the main square for dancing and drumming and feasting on sweets.

The festival extended for multiple days. In quiet morning moments, we continued to explore the city’s famous tourist spots—the Bahia and Badii Palaces, the House of Photography, the Yves Saint-Laurent Jardin Majorelle, the Jardin Secret, and more.

The aptly named Jardin Secret offers a reconstruction of a traditional Islamic garden from the 19th century—these green spaces earned Marrakech its nickname as “an oasis in the desert.” Many of the city’s gardens are structured in four precise quadrants, intersected by tiled walkways, and framed by a central fountain. As the Jardin Secret museum makes clear: “The garden therefore stands as a metaphor for Paradise; it is a holy place, designed to strict geometric rules, where Muslim order is imposed on the disorder of wild nature.”

As is true about nature, Marrakech is defined by a fascinating interplay between randomness and structure, chaos and order.

The aptly named Jardin Secret offers a reconstruction of a traditional Islamic garden from the 19th century—these green spaces earned Marrakech its nickname as “an oasis in the desert.” Many of the city’s gardens are structured in four precise quadrants, intersected by tiled walkways, and framed by a central fountain. As the Jardin Secret museum makes clear: “The garden therefore stands as a metaphor for Paradise; it is a holy place, designed to strict geometric rules, where Muslim order is imposed on the disorder of wild nature.”

As is true about nature, Marrakech is defined by a fascinating interplay between randomness and structure, chaos and order.

Marrakech mirrors itself, in a concentric, repetitive, fractal kind of pattern. The same details that define a single riad or garden—a central fountain, a quadrant structure, a series of arched gateways—also characterize the city as a whole.

“It is said, at the beginning, a well or a spring was located at the very heart of Marrakech, being the meeting point of two perpendiular axes that connected the four gates of the city: the city was the image of the riad, and the riad the image of the city.”

“It is said, at the beginning, a well or a spring was located at the very heart of Marrakech, being the meeting point of two perpendiular axes that connected the four gates of the city: the city was the image of the riad, and the riad the image of the city.”

To walk around the medina is to traverse these beautiful archways. Likewise, to leave the old town, one must exit through one of the many archways that line the outer ramparts.

On the outskirs of the medina is Guéliz, a neighborhood known as the “new city.” Here, the chaos-within-order structure of the medina gives way to a more contemporary town, filled with Art Deco colonial architecture, apartment buildings, and porous international, Western influences.

Elsewhere, in the outer orbits of the city, we found glimpses of Marrakech’s modernist architecture and contemporary art—like the serene and beautiful MACAAL, a museum of African contemporary art, which features stunning environmental justice-focused work from everywhere from Madagascar to Morocco.

Throughout our time, the moon was a main character. After all, the holy month of Ramadan follows the lunar calendar—the Eid-al-Fitr festival always coincides with the New Moon. The city and culture moves in-step with these larger natural rhythms.

Day and night, Marrakech is pulled in a beautiful balance between its dialectic extremes: structure and chaos, order and randomness, ancient and contemporary, indoors and outdoors, private and public, desert and garden.